Note: This post was edited on August 28, 2019 to fix/replace broken links.

Alternate title: acing those placement exams.

Congratulations! You made it past auditions, and now you get to be a fancy masters or doctoral student and live out all your fantasies of striding down the halls of the music building while wee undergrads swivel their heads in awe! Not so fast, though: there’s just one more hurdle to leap over. (As if those applications, pre-screenings, and auditions weren’t enough. But come on, if you wanted life to be easy, you wouldn’t be a musician.)

PLACEMENT EXAMS.

The theory and history placement exams nearly all incoming graduate students will have to take are just preliminary assessments to see where your theory/history level is at. So theoretically, you don’t have to study at all, particularly if (a) you’re a theory/history BAMF and could practically teach a class yourself, or (b) you’re happy to wither away, wasting hours of your life in remedial classes while your peers are practicing, performing, etc.

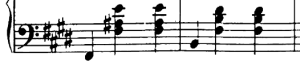

Neither of those options are for me! So, let’s study together! Yay! Here are some resources for your summer reviewing pleasure.